13

The third trial began this August at the Boone County courthouse, two hours north of New Albany. Once again, both families filed into rows for the testimony and evidence they’d heard twice before.

In accordance with the first two appeals, the judge prohibited any testimony about Camm’s affairs or the molestation allegations. He wouldn’t allow the defense to mention Boney’s foot fetish either.

Prosecutors focused on Jill’s blood on Camm’s T-shirt, while the defense argued the basketball players corroborating the man’s alibi had never wavered. Camm’s arrest, the lawyer said, was the result of a botched investigation and a prosecutor with tunnel vision.

On the day Boney testified, officers escorted the man into the courtroom, his hands and ankles shackled against his DOC jumpsuit.

As Camm entered the room, the two men locked eyes and didn’t blink.

The prosecutor asked Boney if he could point out David Camm for the jury.

“Mr. Camm is sitting right there,” Boney said, “in the suit, blue tie, looking very dapper.”

He didn’t flinch. Camm clenched his jaw.

Boney testified that as he handed Camm the gun at his home that night in 2000, Kim pulled into the family’s garage. That’s when Camm followed her up the driveway and the couple started arguing.

He said he heard a “pop!” then a little boy yelling “Daddy!” followed by another “pop!,” and then a third “pop!”

Boney said Camm emerged from the garage, turned the gun on him and tried to shoot, but it jammed. Camm ran toward the house, Boney said, and he chased him into the garage, but Camm disappeared inside. In the pursuit, Boney ran and tripped over Kim’s shoes, he testified, and placed them on top of the truck so nobody else would do the same.

He said he did not touch anyone and fled the scene.

As the trial wound down, an independent forensic scientist from the Netherlands explained how Boney’s touch DNA — a new science — was found on the clothing Kim and Jill wore that night.

On a slow day toward the end of the trial, Donald Camm, David Camm’s father, convinced his family to let him make the two-hour trip north. His declining health forced him to wear an oxygen tank.

When Camm walked into the courtroom, he teared up as soon as he saw his elderly father with the clear tubes in his nose.

That afternoon, the bailiff let the old man spend a few minutes with Camm, handcuff-free. In a back room, they hugged. It was the first time in years Donald had been able to touch his son.

The day of closing arguments, the courtroom was full. Prosecutor Todd Meyer called Camm a murderer and showed the jurors photos of Kim, Brad and Jill.

“You have to wonder where they’d be today,” he said.

Defense attorney Stacy Uliana reminded the jury of the 18 cuts and bruises that had been found on Kim’s body.

“She fought long and she fought hard,” Uliana said. “She fought for her children.”

The courtroom was silent.

“Charles Boney can take away his family,” she said. “The State of Indiana can take away his freedom. But they can’t take away his truth and knowledge.”

She turned to face Camm, who fought back tears.

“And you did everything in your power that night to save your family.”

Quiet sobs sounded from the gallery.

•••

The kitchen staff at Brenda’s Cubbard, a diner across the street from the Boone County Courthouse, knew first there was a verdict. It was Oct. 24, and the courthouse called just after 9:30 a.m. to cancel the jurors’ lunch orders. They’d only deliberated for 10 hours.

The restaurant staff too waited anxiously for a verdict.

In the crowded courtroom, the foreman handed the large manila envelope to the bailiff, who brought it to the bench where the judge pulled out the answer.

Not guilty. Not guilty. Not guilty.

Camm sobbed. He stood up and sat down again, praised God and thanked the jury. As they left the courtroom, some jurors wiped away tears of their own.

Kim’s parents sat frozen in their seats. Her father didn’t move for 20 minutes.

When Camm’s lawyers and family left the building, they were bombarded by television news cameras. How did they feel? What did Camm say? What would they do next?

Coffee, Donald Camm said with a grin. He just wanted some hot coffee.

As police swept David Camm away in a sheriff’s department SUV armed by guards with assault rifles, his family shuffled across the street into Brenda’s Cubbard to escape the biting wind. They’d meet up with him later, where it was safe.

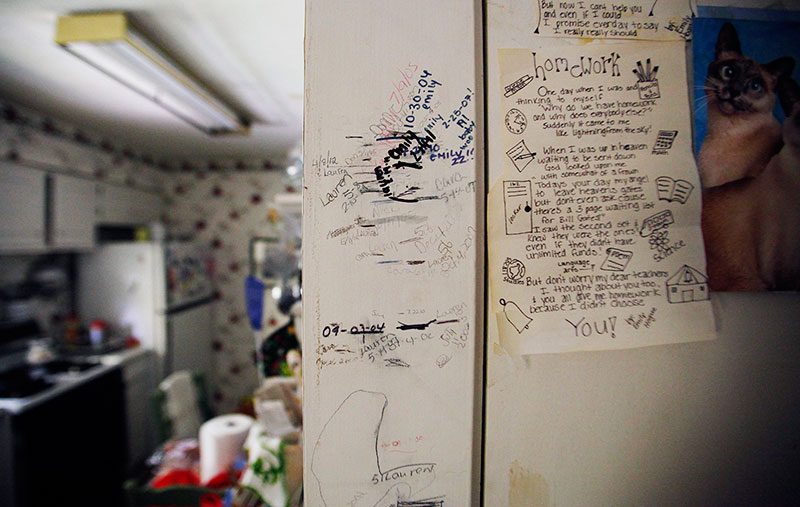

With his mug in front of him, Donald, his family and the restaurant staff joined hands, cried and prayed.

“Amen,” someone said, “and pass the potatoes.”